Home

The history of the firm R.T. Tanner & Co Ltd

Batchelors

A series of articles were produced in the Tanners trade circulars about Hand Made Paper. In what appears to be a close business relationship Batchelor & Sons were featured.

Below is a representation of the articles originally printed from December 1906 to April 1907

Hand Made Paper: Its History and Manufacture

[Extracted Highlight December 1906 Page 209-211]

The use of hand made paper is undoutedly becoming more and more general; for high class work it certainly has no equal, for with it the printer

can give a really artistic finish to his letterpress.It has always been more or less surprising to us that hand made paper has not been more generally

used, especially for work where cost is of little consideration. There are several points that the printer must bear in mind when using this class of paper,but,

in a future issue we hope to give full particulars for working.

The use of hand made paper is undoutedly becoming more and more general; for high class work it certainly has no equal, for with it the printer

can give a really artistic finish to his letterpress.It has always been more or less surprising to us that hand made paper has not been more generally

used, especially for work where cost is of little consideration. There are several points that the printer must bear in mind when using this class of paper,but,

in a future issue we hope to give full particulars for working.

The present day revival, if such it might be called, commenced with Mr Ruskin promulgating his doctrines of hand labour in preference to machine labour, but the

honour falls on Mr William Morris for having brought such papers into practical use, in his connection with the Kelmscott Press. Others have continued the work

commenced by Morris, with the result that hand made paper has received a fair amount of attention, especially by those who are endeavouring to raise, in the

truest sense of the word, the standard of the Craft.

Seeing, then, the importance of the subject, we thought it would not be out of place to give our readers some account of the history of hand made paper, together with

its process of manufacture; for we felt that the latter especially would be read with extreme interest by every modern printer. With this thought in our mind we approached

Mr Batchelor, of the Ford Paper Mill, Little Chart, Kent, and after explaining our object, we found that he was quite willing to fall in with our suggestions, with all the enthusiasm

at his command. We visited the Mill, and had every process in the manufacture of the paper carefully and consciously explained to us, nothing, so far as we could see, being kept back.

It is the information gained on this occassion that we hope to give in the pages of our Trade Circular throughout the next few issues. When we state that it was at the above Mill

that the paper was made for the Kelmscott Press, and where it is now being made for the Cardoc Press and other important printers and publishers, no further introduction is necessary

in proof of the genuine high class quality of the Mill's products. Messrs Batchelor & Son not only make printing papers, but they also specialise in blue and cream account book papers, but

we shall have more to say about these products in future issue. Before proceeding further, we must express our appreciation for the very kind way we were received by Mr Batchelor, and for

the facilities afforded us of securing just the kind of information which we felt would be welcomed by our readers.

Mr Batchelor, of the Ford Paper Mill, Little Chart, Kent, and after explaining our object, we found that he was quite willing to fall in with our suggestions, with all the enthusiasm

at his command. We visited the Mill, and had every process in the manufacture of the paper carefully and consciously explained to us, nothing, so far as we could see, being kept back.

It is the information gained on this occassion that we hope to give in the pages of our Trade Circular throughout the next few issues. When we state that it was at the above Mill

that the paper was made for the Kelmscott Press, and where it is now being made for the Cardoc Press and other important printers and publishers, no further introduction is necessary

in proof of the genuine high class quality of the Mill's products. Messrs Batchelor & Son not only make printing papers, but they also specialise in blue and cream account book papers, but

we shall have more to say about these products in future issue. Before proceeding further, we must express our appreciation for the very kind way we were received by Mr Batchelor, and for

the facilities afforded us of securing just the kind of information which we felt would be welcomed by our readers.

And now a word or two in respect to the History of Hand Made Paper. Of course the history of such papers is the same as the history of the commodity itself until machinery was introduced

in its manufacture. As we have already dealt with this subject in our pages, our remarks must be as brief as possible. The making of paper from the cotton plant was practised by the Chinese

in very remote periods, and it was introduced from Asia into Europe about the year 740. The Egyptians used papyrus leaves for their writings, so that this name was given to the material made from

cotton plant. There are many MSS, now extant which were written on paper made during the ninth century. The oldest document on cotton paper is a deed by the King of Sicily dating from 1102, and in the

British Museum we have examples of paper dating from the first half of the 13th Century.

The Moors seem to have been the first makers of paper in Europe, their products being made exclusively from cotton. Wool and linen were subsequently used in conjunction with cotton, and during

the 14th Century we find the first use of watermarks in paper. The industry gradually spread from Spain to Italy, and then through Germany and France, and eventually to England. The texture of the early

paper was coarse, and the wire marks very large; the water marks were at first simple in design, but gradually became more elaborate and ornate. During the 15th Century the paper became finer, but it was

extremely tough.

Paper was certainly used in our own country at the beginning of the 14th Century, being imported from Spain, as the earliest record of an English maker is in the early part of the 16th Century, a mill being then

started at Hertford. Although no other mills are known to have existed, the general use of paper, and its comparative cheap price in the 15th Century, would indicate that its manufacture, to some considerable extent,

must have been carried on in England. Down to 1804, when machinery was first introduced, all the paper was made by hand, much in the same way as it is today at the Kent Mills. As in other branches of commercial enterprise,

the introduction of machinery gave a new impetus to the industry, but it caused hand made papers practically to fall into disuse. A revival, however,

is taking place, as we have already hinted, and it is therefore advisable for every printer to be alive to the movement, so that he may keep abreast of the times.

[Extracted Highlight January 1907 Pages 229-231]

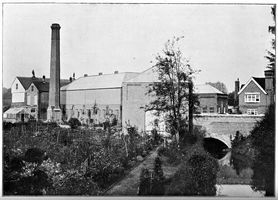

The Ford Paper Mill is situated in the very heart of "the Garden of England" being about ten miles from Charing and four miles from the market town of Ashford. We made our visit early in November, and as we

drove along the rural roads we were much impressed by the beauty of the country through which we had to pass. Owing to the abnormally mild weather we have experienced this year, everthing was resplendent in

autumal tints, or as Lowelsays of this time of year "Autumn is the poet of the family. It gets you of a splendour that you would say was made out of real sunset." And so it was on the day we visited the Ford Mill:

the fields were ablaze with gold and russet from the fallen leaves, and as the trees were by no means bare, the colours seemed to be carried into the sky. On arrival at Little Chart, we were greeted by the the

cheery voice of Mr Batchelor, and whilst we were partaking of light refreshments (? light), for Mr Batchelor's residence adjoins his mill, he gave us a short history of the concern.

The Ford Paper Mill is situated in the very heart of "the Garden of England" being about ten miles from Charing and four miles from the market town of Ashford. We made our visit early in November, and as we

drove along the rural roads we were much impressed by the beauty of the country through which we had to pass. Owing to the abnormally mild weather we have experienced this year, everthing was resplendent in

autumal tints, or as Lowelsays of this time of year "Autumn is the poet of the family. It gets you of a splendour that you would say was made out of real sunset." And so it was on the day we visited the Ford Mill:

the fields were ablaze with gold and russet from the fallen leaves, and as the trees were by no means bare, the colours seemed to be carried into the sky. On arrival at Little Chart, we were greeted by the the

cheery voice of Mr Batchelor, and whilst we were partaking of light refreshments (? light), for Mr Batchelor's residence adjoins his mill, he gave us a short history of the concern.

It appears that it dates back to 1776, when it was established as a one vat paper mill, but it passed through several hands, until a century later it was taken over by the present proprieter. From practically

nothing more than farm buildngs, Mr Batchelor has converted it, step by step, into the present up to date mill, replete with electric light and every modern convenience. It comprises several buildings, all

erected on the most approved plans; and they are so arranged that the whole of the machinery can be run either by water power or by steam. As is essential to every paper mill, there is a plentiful supply of good

water, which is "stored" in an adjoining lake.

Not only did Mr Batchelor give us the above outline, but we also gleaned something about the man himelf. First and foremost, he is, in every sense of the word, a practical man, and can carry out any process in hand

made paper making better than any of his employees. He served his apprenticeship making Whatman paper, and this practical side of his nature he has inculcated into his son, who assists him in the business, so that

Mr Batchelor, jun., like his father, knows all the ins and outs of the trade. We shall have more to say on this subject in a future but we might mention en passent that had hand made paper was made at the inception

of the Ford Mill, and to this day it is the only kind of paper that is sent out from Little Chart.

Not only did Mr Batchelor give us the above outline, but we also gleaned something about the man himelf. First and foremost, he is, in every sense of the word, a practical man, and can carry out any process in hand

made paper making better than any of his employees. He served his apprenticeship making Whatman paper, and this practical side of his nature he has inculcated into his son, who assists him in the business, so that

Mr Batchelor, jun., like his father, knows all the ins and outs of the trade. We shall have more to say on this subject in a future but we might mention en passent that had hand made paper was made at the inception

of the Ford Mill, and to this day it is the only kind of paper that is sent out from Little Chart.

[Extracted Highlight February 1907 Pages 11-15]

We have now arrived at the stage when we must begin to describe the process of hand made paper making from a practical standpoint. To one who has never seen the process it must be of particular interest, and even

to those who are familiar with the manufacture of paper, there are certain details connected with the hand method which always appear more or less mysterious. We shall endeavour to follow the process step by step

so as to try and make it clear, even to those who have never had an opportunity of going over a paper mill of any kind whatever.

We have now arrived at the stage when we must begin to describe the process of hand made paper making from a practical standpoint. To one who has never seen the process it must be of particular interest, and even

to those who are familiar with the manufacture of paper, there are certain details connected with the hand method which always appear more or less mysterious. We shall endeavour to follow the process step by step

so as to try and make it clear, even to those who have never had an opportunity of going over a paper mill of any kind whatever.

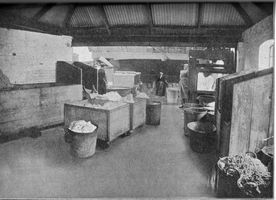

The raw material used in the manufacture of hand made paper is, of course, rags of various kinds according to the quality of the paper desired, linen, cotton and muslin being the most generally used. All the rags

as they are received at the mill go first through a process of rough dusting in order to cleanse them from as much dirt as possible. This process is done mechanically, the machine for the purpose being called a

Rough Duster. It consists of an extremely large revolving metal drum, which is more or less conical in shape. This causes the rags to travel from one end of the drum to the other end, and, as they do so the dust

is beaten out. This falls out in clouds, but, by a special arrangement of fans, and owing to the drum being encased in a wooden chamber, the dust is carried away, with the result that the room in which this work

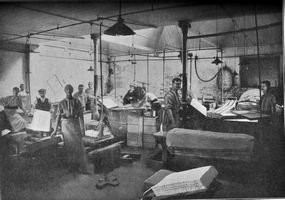

is done is quite healthy, and as free from dust as any other department. All the rags, after having been cleaned in this way, are classified and cut either by hand or by machinery. The former method is employed

for the best papers, whereas the latter method is used for paper of cheaper quality. The machine cutter is in the same room as the Rough Duster, but the hand cutting is carried on in a separate department, a corner

of the room being shown in one of the accompanying illustrations. At the time of our visit this department presented a very busy appearance. A number of women were engaged cutting the rags into small pieces; each one

stands at a bench, and in front of her there is fixed an upright knife, somewhat of the same shape as a sickle, but having a smaller curve. The space on the bench around the knife is left open, except that it is covered

with a piece of perforated zinc which allows the dust, made in the process of cutting, to fall away from the bench. Needless to say these knives are kept exceptionally sharp, and the rapidity with which the women

work is wonderful.

The raw material used in the manufacture of hand made paper is, of course, rags of various kinds according to the quality of the paper desired, linen, cotton and muslin being the most generally used. All the rags

as they are received at the mill go first through a process of rough dusting in order to cleanse them from as much dirt as possible. This process is done mechanically, the machine for the purpose being called a

Rough Duster. It consists of an extremely large revolving metal drum, which is more or less conical in shape. This causes the rags to travel from one end of the drum to the other end, and, as they do so the dust

is beaten out. This falls out in clouds, but, by a special arrangement of fans, and owing to the drum being encased in a wooden chamber, the dust is carried away, with the result that the room in which this work

is done is quite healthy, and as free from dust as any other department. All the rags, after having been cleaned in this way, are classified and cut either by hand or by machinery. The former method is employed

for the best papers, whereas the latter method is used for paper of cheaper quality. The machine cutter is in the same room as the Rough Duster, but the hand cutting is carried on in a separate department, a corner

of the room being shown in one of the accompanying illustrations. At the time of our visit this department presented a very busy appearance. A number of women were engaged cutting the rags into small pieces; each one

stands at a bench, and in front of her there is fixed an upright knife, somewhat of the same shape as a sickle, but having a smaller curve. The space on the bench around the knife is left open, except that it is covered

with a piece of perforated zinc which allows the dust, made in the process of cutting, to fall away from the bench. Needless to say these knives are kept exceptionally sharp, and the rapidity with which the women

work is wonderful.

After being cut, either in the above way or by machinery, the rags are transferred to another process of dusting in what, in technical parlance, is termed a Willow Duster. This is somewhat similar to the Rough

Duster except that it is fixed inside. In this way the rags are knocked about more than in the first process, with the result that a large amount of fluff collects, even with a few hands full of rags. This is

ingeniously collected and resold for other purposes, so there is nothing wasted.

After being cut, either in the above way or by machinery, the rags are transferred to another process of dusting in what, in technical parlance, is termed a Willow Duster. This is somewhat similar to the Rough

Duster except that it is fixed inside. In this way the rags are knocked about more than in the first process, with the result that a large amount of fluff collects, even with a few hands full of rags. This is

ingeniously collected and resold for other purposes, so there is nothing wasted.

Arrived at this stage, the rags appear to be quite clean, but they are then boiled by steam for from four to eight hours, according to the class of rags, in large iron vats. After the process of boiling, they are

coverted into pulp, but we must deal with this portion of our subject in another issue.

[Extracted Highlight March 1907 Pages 35-39]

In our last article we dealt with the process of Dusting and Boiling, the object of the latter process being, not only to remove the dirt in the rags, but also to decompose other substances in them which would

impair the flexibility of the fibres. The most interesting processes, however, in connection with hand made paper making, are those which follow, namely, the changing of the rags into pulp, and the conversion of the

pulp into paper.

In our last article we dealt with the process of Dusting and Boiling, the object of the latter process being, not only to remove the dirt in the rags, but also to decompose other substances in them which would

impair the flexibility of the fibres. The most interesting processes, however, in connection with hand made paper making, are those which follow, namely, the changing of the rags into pulp, and the conversion of the

pulp into paper.

The next step after Boiling is that of Washing and "Breaking in", which is done in a machine called the "Breaker". It consists of a heavy iron roll, provided with knives, which works in a large oval shape trough

or tank. The machine is half filled with water and then packed with the boiled rags, where they are washed and rubbed for about four hours. A fresh supply of clean water is constantly running into the "Breaker", and

the superfluous dirty water in the machine is being withdrawn continuously by the "washer". On the completion of this process the "stock" consists of finely divided particles or threads suspended in the water, having

somewhat the appearance of wool. From the "Breaker", the pulp is conveyed to the Bleach House, and then removed to the "Beating" engine, which is very similar in design to the Breaker. The action, however, is slower, and by

a series of revolving knives and serrated edges, the fibres are drawn out into a very fine estate. Unlike the former process, there is no continuous supply of fresh water entering the "Beater", and it is during

this process that smalt, (which is a fine blue oxide of cobalt, and reduced to an impalpable powder) is added, when the paper has to be, for instance, of an azure colour.

The pulp is then stored in chests, from which the vat is supplied. The Vat House is of particular interest, for it is here where the pulp is kept constantly moving, and the vatman takes a mould or rectangular tray, on

the top of which are stetched parallel wires with others at right angles. On this is tightly held a "deckle" or wooden frame. As he withdraws the mould out of the vat in a horizontal plane, the water within the deckle

drains off, leaving the wires coated with fibre; a peculiar shake is then given to the mould, which has the effect, when rightly done, of distributing the fibres evenly. It is just here where the art of paper making

comes in. We tried the process, taking off our coat and rolling up our sleeves in the true spirit of the British workman, but that shake or twist, or whatever one likes to call it, was too much for us. To see Mr. Batchelor

do it, the thing seemed simplicity itself, but in the hands of the uninitiated the fibres seem to go any way but the right way. However, we took courage, for on asking one of the workmen how long it had taken him to

learn the art, he replied that he had been at it fifty years and he was still learning. When one comes to consider that the vatman can dip his frame hundreds of times, and yet the resulting sheet of paper does not

vary in weight even by a few grains, the amount of dexterity required can better be imagined than described. When a watermark is required in the paper, it is produced by wires, representing the design or letters, being

raised slightly above the rest of the mould. The paper is therefore thinner in these parts, and the letters can in consequence be read when the sheet is held up to the light, as can also the wire of the mould.

The pulp is then stored in chests, from which the vat is supplied. The Vat House is of particular interest, for it is here where the pulp is kept constantly moving, and the vatman takes a mould or rectangular tray, on

the top of which are stetched parallel wires with others at right angles. On this is tightly held a "deckle" or wooden frame. As he withdraws the mould out of the vat in a horizontal plane, the water within the deckle

drains off, leaving the wires coated with fibre; a peculiar shake is then given to the mould, which has the effect, when rightly done, of distributing the fibres evenly. It is just here where the art of paper making

comes in. We tried the process, taking off our coat and rolling up our sleeves in the true spirit of the British workman, but that shake or twist, or whatever one likes to call it, was too much for us. To see Mr. Batchelor

do it, the thing seemed simplicity itself, but in the hands of the uninitiated the fibres seem to go any way but the right way. However, we took courage, for on asking one of the workmen how long it had taken him to

learn the art, he replied that he had been at it fifty years and he was still learning. When one comes to consider that the vatman can dip his frame hundreds of times, and yet the resulting sheet of paper does not

vary in weight even by a few grains, the amount of dexterity required can better be imagined than described. When a watermark is required in the paper, it is produced by wires, representing the design or letters, being

raised slightly above the rest of the mould. The paper is therefore thinner in these parts, and the letters can in consequence be read when the sheet is held up to the light, as can also the wire of the mould.

The mould of fibres, or the sheet of paper as we must now term it, is laid by the vatman on an inclined board, which it runs down to another workman called the "coucher". He turns the paper out of the mould on to a

sheet of felt, and piles paper and felt alternately together, until he secures, what in technical phraseology, is termed a "post". The felt absorbs some water, but the "posts" are placed under hydraulic pressure,

which presses out a large amount of water, and leaves the sheets sufficiently dry for them to be handled by what is known as the "layer". The paper is placed in piles one sheet above another, when they are again

pressed, this process sometimes being repeated for three times, but between each pressure the paper is parted sheet from sheet. The next process is that of drying, but this we shall describe in our next issue.

The mould of fibres, or the sheet of paper as we must now term it, is laid by the vatman on an inclined board, which it runs down to another workman called the "coucher". He turns the paper out of the mould on to a

sheet of felt, and piles paper and felt alternately together, until he secures, what in technical phraseology, is termed a "post". The felt absorbs some water, but the "posts" are placed under hydraulic pressure,

which presses out a large amount of water, and leaves the sheets sufficiently dry for them to be handled by what is known as the "layer". The paper is placed in piles one sheet above another, when they are again

pressed, this process sometimes being repeated for three times, but between each pressure the paper is parted sheet from sheet. The next process is that of drying, but this we shall describe in our next issue.

[Extracted Highlight April 1907 Pages 59-63]

The process of drying requires great care in order to obtain the most satisfactory sizing later on, and must be done slowly, with as much air passing through the paper mill as is possible, otherwise unequal contraction

will take place and a want of toughness. When completely dry, the paper is sized by passing the "spurs" through a solution of gelatine, contained in the sizing machine. The machine occupies the whole of one room and is

fed at one end, the paper passing along on an endless felt to the other end, being immersed some thirty minutes, when it is taken from the machine. The sheets are immediately separated to prevent them from sticking

together, and then have to be carefully dried. The drying of sized paper is a very delicate process, and requires a great amount of care, in order to secure the best results. The sheets are hung on racks in the Drying

Room, in "spurs" of three to five sheets thick according to the substance. When the racks are filled with the damp paper, the room is closed up, and the temperature inside is very gradually raised until the sheets are

perfectly dry. On no account must the temperature be allowed to fall during the whole of the time that the sheets are drying, nor must the room be allowed to get too warm, and humid, for in both cases, the result is the

same:- unsatisfactory paper. In this condition the paper has a very rough surface, and in order to give it the necessary finish, it is glazed by means of boards, after having been first passed through a Rolling Press. The

rapidity with which this is done is remarkable, and the workmen must require years of patient labour in order to make them proficient in the work. By merely passing the sheets of paper, individually, between two glazed

boards, their appearance is entirely changed, and we were informed that varying surfaces may be secured by using different plates both for rolling and glazing. Each sheet of paper is then most carefully examined, and afterwards

packed up into ream parcels, in which condition it is ready for sale.

The process of drying requires great care in order to obtain the most satisfactory sizing later on, and must be done slowly, with as much air passing through the paper mill as is possible, otherwise unequal contraction

will take place and a want of toughness. When completely dry, the paper is sized by passing the "spurs" through a solution of gelatine, contained in the sizing machine. The machine occupies the whole of one room and is

fed at one end, the paper passing along on an endless felt to the other end, being immersed some thirty minutes, when it is taken from the machine. The sheets are immediately separated to prevent them from sticking

together, and then have to be carefully dried. The drying of sized paper is a very delicate process, and requires a great amount of care, in order to secure the best results. The sheets are hung on racks in the Drying

Room, in "spurs" of three to five sheets thick according to the substance. When the racks are filled with the damp paper, the room is closed up, and the temperature inside is very gradually raised until the sheets are

perfectly dry. On no account must the temperature be allowed to fall during the whole of the time that the sheets are drying, nor must the room be allowed to get too warm, and humid, for in both cases, the result is the

same:- unsatisfactory paper. In this condition the paper has a very rough surface, and in order to give it the necessary finish, it is glazed by means of boards, after having been first passed through a Rolling Press. The

rapidity with which this is done is remarkable, and the workmen must require years of patient labour in order to make them proficient in the work. By merely passing the sheets of paper, individually, between two glazed

boards, their appearance is entirely changed, and we were informed that varying surfaces may be secured by using different plates both for rolling and glazing. Each sheet of paper is then most carefully examined, and afterwards

packed up into ream parcels, in which condition it is ready for sale.

From the above remarks, we trust that we have described the processes so as to be understood by all; it will readily be seen that the expense of manufacturing paper in this way, must of necessity be considerably greater

than by machinery. Throughout, there is a great amount of skill required to secure, the end in view, namely, a paper that shall be extremely strong, and have an ideal texture and surface, either on the one hand for

letterpress work, or on the other hand, for writing. Mr Batchelor explained to us that the strength was obtained through the fibres knitting together in a reticulate manner, owing to the pulp being taken from the vat

(as explained in a previous issue) and pressed, instead of being drawn out into elongated threads as must be the case when made by machinery, from the continual "pull" on the paper in one direction.

From the above remarks, we trust that we have described the processes so as to be understood by all; it will readily be seen that the expense of manufacturing paper in this way, must of necessity be considerably greater

than by machinery. Throughout, there is a great amount of skill required to secure, the end in view, namely, a paper that shall be extremely strong, and have an ideal texture and surface, either on the one hand for

letterpress work, or on the other hand, for writing. Mr Batchelor explained to us that the strength was obtained through the fibres knitting together in a reticulate manner, owing to the pulp being taken from the vat

(as explained in a previous issue) and pressed, instead of being drawn out into elongated threads as must be the case when made by machinery, from the continual "pull" on the paper in one direction.

Not only does Messrs Batchelor and Son make a speciality of hand made for printing, such for example as the quality used for the February issue of our Journal, but they also make papers suitable for account books and writings.

For really high class work, and where longevity is wanted, their paper cannot be beaten.

In conclusion, we might mention that the Ford Mills are lit throughout by electricity generated on the premises; this can also be used for driving the machinery, whenever the occassion arises. In juxtaposition to the mill

there is a large lake, so that they have an inexhaustible supply of really good water, which, as we have already shown is of great importance in the manufacture of hand made paper. The works are situated admist

beautiful surroundings, and every department seems to have been carefully designed, not only for the conveyance of the firm, but also with regard due to the comfort of the employees.